Theoretical physicist John Cardy was a student at Cambridge during Paul Dirac's last year as a professor, and still remembers him to this day. Cardy also recalls that Dirac's book "The Principles of Quantum Mechanics" was a great inspiration for him as a physicist. That was about 40 years ago. Now, Cardy works at Oxford University, and he joined Edouard Brézin of Ecole Normale Supérieure in France and Alexander B. Zamolodchikov of Rutgers University in New Jersey, USA, in receiving the prize that carries Dirac's name.

All three recipients of the 2011 Dirac Medal came together at ICTP to receive the award on Tuesday, 10 July. Their work on quantum field theory has had an impact on fields such as string theory, statistical physics, probability theory, condensed matter physics and symmetry theory.

Brézin's work was critical to developments in field theory in the 1970s. His work includes the discovery that during phase transitions -- critical junctures when matter changes its state such as a liquid evaporating into a gas -- matter behaves similarly over different scales. "What you find," said Brézin, "is that no matter what microscope you use, you see the same thing, all over."

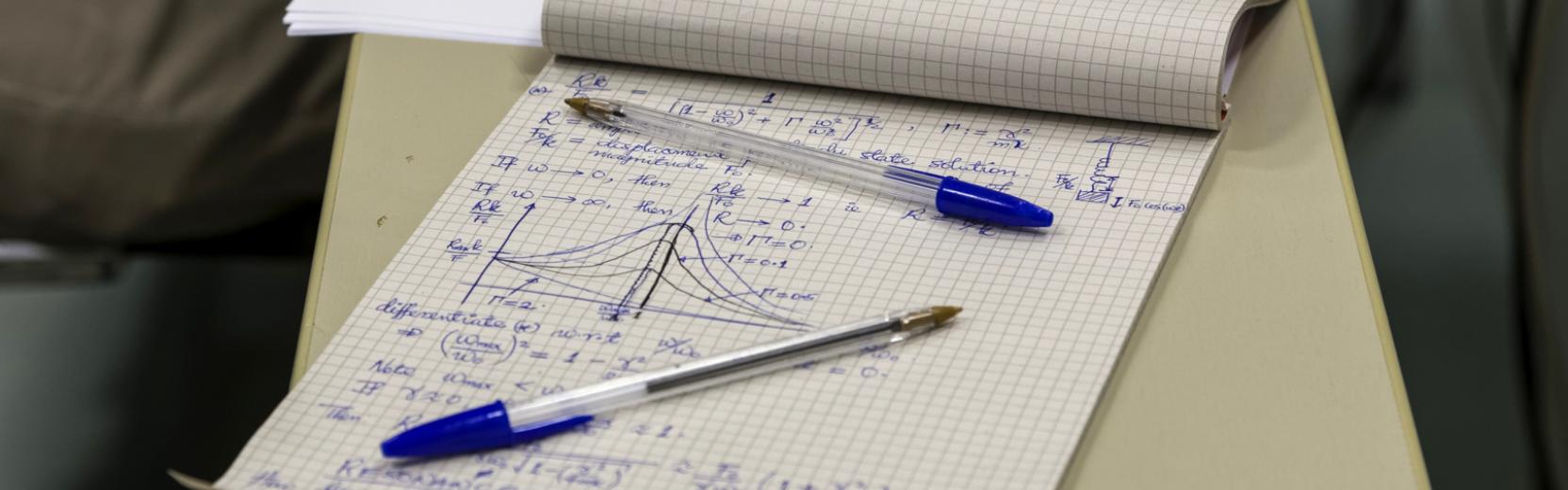

Zamolodchikov's work followed after he became intrigued by quantum field theory. "I was a student and the whole subject sounded very messy to me," he said. "I tried to sort it out and I started to look for simpler models or versions of what was going on." Zamolodchikov boiled the theory down to only two dimensions, presenting physics with a powerful tool that has since become part of the mathematical infrastructure within modern-day string theory. String theory is an attempt to bind the relativistic rules of enormous objects with the quantum rules of tiny particles using hypothetical vibrating one-dimensional objects called strings.

Cardy credits Zamolodchikov's work on two-dimensional quantum field theory with inspiring his own work. Cardy took the two-dimensional systems and modified them, for example by placing boundaries on otherwise infinite dimensions. Just thinking about these variations gave rise to further theories. "This turned out to be important for string theory, though I wasn't inspired by string theory. I'm not a string theorist," Cardy said. "I think it's an example of how you can start by just thinking about a theory and how it fits together, and the applications kind of drop out."

All three recipients observed that barriers between fields of physics seem to be fading, as physicists focus on unifying their field across all specialties. They also hailed the importance of curiosity-driven science in their work. "It's the internal beauty and consistency that has always driven all of us," said Brézin. He later added a remark on receiving the Dirac Medal: "I was thrilled I must say. It's a case where sharing doesn't withdraw anything, and on the contrary it adds to it a lot."

ICTP's Dirac Medal, first awarded in 1985, is given in honour of P.A.M. Dirac, one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century and a staunch friend of the Centre. It is awarded annually on Dirac's birthday, 8 August, to scientists who have made significant contributions to theoretical physics. The Medallists also receive a prize of US$ 5,000. The Dirac Medal is not awarded to Nobel Laureates, Fields Medallists, or Wolf Foundation Prize winners, although many Dirac Medallists have proceeded to win these prestigious prizes.

For more details about the Dirac Medal, visit its webpage.