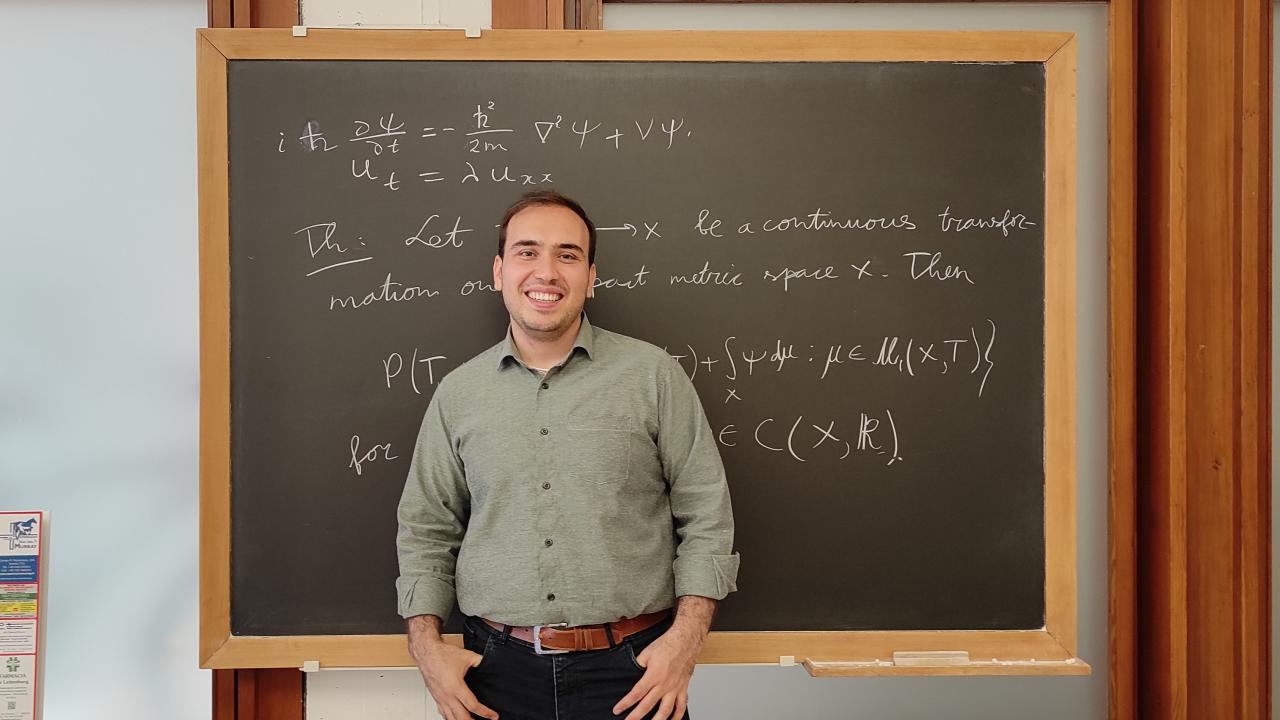

Saeed Azizi is one of the more than 1000 students who graduated from ICTP's Postgraduate Diploma Programme, which celebrated its 30th anniversary this week. Azizi enrolled in the Quantitative Life Sciences section of this year's Diploma class and graduated on 25 August with a thesis in Neuroscience and Machine Learning, studying computational methods to investigate the vision system of rats, under the supervision of Professor Davide Zoccolan of SISSA and ICTP researcher Jean Barbier.

Azizi, born in Afghanistan, has lived in Iran since he was a child, where he and his family looked for shelter after fleeing their home country, occupied by the Taliban. He has overcome many difficulties, and is now hoping to apply what he learned during the intense year of study at ICTP to build a career in academia.

ICTP spoke to Azizi about his educational journey and the challenges he has had to overcome to pursue his love of science.

While you were preparing for your thesis defence and your graduation, bad news arrived from your home country. What was your reaction?

Unfortunately, we people of Afghanistan are used to this kind of bad news, particularly in the last forty years. My personal experience, however, may be different from that of many Afghans who still live in the country at the moment. My family and I left Afghanistan when I was four years old, almost 25 years ago now, exactly when the Taliban took over one of the largest cities in the country, Mazar-i-Sharif. We understood that they were also going to take the capital very soon and we had lost all hope that the government could stay in power and defeat the Taliban. We had no hope of being able to continue living in our country, so we went to Iran, and we have lived there for many years.

In Iran it wasn't easy for us. For example, when we arrived we did not even have the right to go to school and there were very strict rules against immigrants like us, we were relegated to the lowest level of society. In addition to this, we had restrictions in choosing what to study at university, and in which city. Personally, I was interested in studying physics, so for me these restrictions were even more serious. I was interested in studying atomic and molecular physics, but I wasn't allowed to enroll in that course because it was considered a sensitive field. I had little choice, so I ended up studying a different field - solid state physics.

In some respects my experience in a foreign country was worse compared to that of those who stayed in Afghanistan. At least there I would have had the right to free education. Of course, in Iran we were safer, because there was no fighting around us, there were no explosions, but I certainly did not have an easy life.

How did you manage to achieve your level of education despite all of these difficulties?

In the beginning, when we arrived in Iran, self-ruled schools were formed. They were very simple settings where people just tried to give an education to children. After a while, however, the Iranian government closed them for security reasons. Then me and my siblings managed to attend the classes in an Iranian school even if we were not able to do it officially, so at the end of the year we were not receiving any regular transcript. Starting from the ninth year of school, however, things changed and I was finally allowed to go to a regular school, but I had to take an exam to prove that I had learned everything from the previous nine years.

What are you studying now?

After studying solid state physics, I specialized in photonics for my master's degree, where I could finally study lasers and optics. Then, last year I finally arrived at ICTP in Trieste to attend the Diploma Programme. I enrolled in the Quantitative Life Sciences section, were I am studying computational methods applied to the life sciences and in particular machine learning. During my master's in Iran I worked on an advanced fluorescence microscopy technique, an extremely modern technology that employs a good component of machine learning techniques to extract information from biological samples. These are sophisticated tools and very advanced technologies that are used in important cutting-edge research, such as the search for vaccines for the coronavirus.

Have you visited Afghanistan since your family left 20 years ago?

I actually went back to Afghanistan for a short time. After my bachelor's degree six years ago, I returned to Kabul for a year to teach in a high school. I took part in a United Nations programme, which consisted of involving young and educated Afghans and supporting them for some time to go back to the country to contribute and benefit the society. It was a good experience, because even though I had been away from my country for many years, I adapted immediately. After growing up in a foreign country, when I returned to Kabul I felt that I belonged to that land and to that people. I was teaching computer science and physics in a nice school, with good resources and facilities, with enough computers for the students and nice classrooms. But there was still deficiency of very simple things. The lack of safety was totally obvious, for example. There were police at the entrance of the school to check the students every day, to avoid any kind of attack to the school by terrorists. Sometimes I could hear explosions near the school, or near my apartment. Those explosions were horrific and hundreds of people were killed or injured. Kabul is like a battlefield, everywhere you could see armed policemen, monitoring everything and everyone and trying to prevent any kind of terrorist action.

How do you think the situation is in Afghanistan now?

This feeling of being unsafe is always present in Afghanistan, and people are tired of feeling unsafe. For example, when I was in Kabul I always used to take the same route to go to the school where I taught. Exactly one month after leaving Kabul there was an explosion on exactly that road and at exactly the same time I used to walk through it. I was lucky not to be there. It is very hard for people to live there, because they are never sure that if they leave the house in the morning they will return in the evening. And this feeling of being in constant danger is a terrible feeling.

What are your plans for the future? Are you planning to return to Afghanistan?

Having grown up for more than 20 years in a culture that felt different from mine and that didn't allow me to feel at home, I have always been very interested in returning to Afghanistan sooner or later. But after my experience in Kabul, although it was great to meet the people, who are nice, kind and hospitable, I felt that life in Afghanistan is too risky, the government too corrupt, that it seemed impossible to me to stay and I went back to Iran.

Now, I have been in Italy for a year, and so I have lost my right to return to Iran, because unfortunately my permit has expired. So I'm in a stalemate, I don't know where I will go next: I can't go back to Iran due to bureaucracy and, with what's happening in Afghanistan, I can't go back there. As you may have seen on television, people are trying to escape from Afghanistan, I don't think I should go back now.

Fortunately, ICTP extended my stay for other three months to allow me to find a PhD position, which was my initial goal anyway, perhaps in Europe, to continue my career in research. From the beginning of my time here at ICTP, I found that everybody was very kind and respectful. I must say though, that at the same time they are very strict, the courses are very fast and the time is limited, so we are expected to give our best and this puts a lot of pressure on us. But the professors and supervisors are extremely supportive. We are provided with everything we need every day, so the only thing we had to do is focus on our study.

About the Postgraduate DIploma Programme

ICTP's Postgraduate Diploma Programme is designed to assist students from least advantaged countries who come from various educational backgrounds and are interested in further, advanced study in physics or mathematics. The programme offers five areas of instruction: high energy physics, condensed matter physics, mathematics, Earth system physics, and quantitative life sciences.

More than 1000 students have graduated from the Postgraduate Diploma Programme since it began in 1991. Of these students, more than a quarter are female. Hundreds of Diploma graduates have gone on to earn PhDs from international universities, mainly in Europe and in the United States, and then have returned to their home countries to put their acquired skills to good use, by becoming teachers or researchers, and thus supporting ICTP's mission to promote advanced scientific research for all.

--- Marina Menga