Every year, ICTP's Salam Distinguished Lecture Series invites an active, respected scientist to speak at ICTP on recent developments in their respective fields. As the 2020 speaker, Marc Mézard did just that, examining the rapid development of artificial intelligence, the spin glass cornucopia, and the future of statistical physics and machine learning.

Mézard, Director of the École normale supérieure in Paris, France, began his series of three Salam Distinguished Lectures with a wide-ranging discussion of artificial intelligence (AI). "Right now my research is completely focused on questions of learning in deep neural networks, which is at the heart of the progress in recent years in AI,” says Mézard. His talk covered the science underlying AI, including the aspect he is working on now: "how the recent succes of deep learning and deep neural networks can be related to the structure of data and the structure of the task that they have to solve. This is one aspect that has not been touched by theory so far, but I think it's absolutely crucial."

The societal impact of using AI technologies was also featured in the talk. "I think the representations many people have of the dangers and threats of AI in general are very wrong," says Mézard. “We are extremely far away from any kind of general artificial intelligence running everything, it is still science fiction, but for very specific tasks and uses, the threat is real.” An audience question after his talk asked what threats Mézard believed were the most pressing, to which Mézard highlighted two worrying uses. One was tools that can be and already are being used for societal surveillance and control, such as facial recognition. The other was AI skill at image analysis being built into autonomous tools of war, creating robots capable of making decisions to shoot without human input.

The road to discussing AI’s implications for society started in statistical physics for Mézard. “I grew up as a scientist studying the science of collective behaviours, trying to understand when you have many elementary components, how their collective behaviour can bring new phenomena,” he says. In the 1970s and 1980s, many statistical physicists were trying to develop tools to study strongly disordered systems, systems in which each component has a different action, levels of complexity that bring completely new emergent behaviour.

Mézard was examining these systems and behaviours in systems of spin glasses, starting with his PhD at the École normale supérieure (ENS) in Paris, France, and subsequently when he became a professor of physics at ENS in 1987. A specific type of magnet, different from the more common ferromagnetic magnets, spin glasses are composed of atoms with their spins, their north and south poles, oriented in a big mix of different directions. As Mézard and his collaborators developed tools to study spin glasses, “pretty soon it appeared to a number of us that these tools could be very useful in various branches of science outside of spin glasses,” says Mézard. “From finance with the study of markets, various aspects of biology, neurobiology with the study of neural networks, gene expression networks, all kinds of systems in physics, glassy systems, structural glasses, spin glasses, electron glasses, etc,” says Mézard. “And there are a myriad of other applications in other branches of science.” That myriad became known as the spin glass cornucopia, the subject of Mézard’s second talk at ICTP.

This wide ranging number of applications was quite unexpected: “In the beginning, we didn’t have any idea of the spin glass cornucopia, not at all,” says Mézard. “But this was a larger goal: I was really focused on trying to understand very tiny, specific, and dedicated aspects of spin glass theory, and that kept us busy for quite some time.” The spin glass cornucopia was a welcome fortuity, however: “It gave me the opportunity to interact with people from very different fields and try to contribute,” says Mézard.

Some of Mézard’s collaborators in the spin glass work have strong connections to ICTP, as does Mézard. Giorgio Parisi of the Sapienza Università di Roma won the ICTP Dirac Medal in 1999, for his original and deep contributions to many areas of physics. Miguel Ángel Virasoro, an Argentine physicist who now teaches alongside Parisi at Sapienza, was the Director of ICTP from 1995 to 2002. The three collaborators co-wrote a book in 1987, and it was with that book that “we started to see that there could be broader applications of our work in spin glasses,” says Mézard. He has returned often to ICTP to work with colleagues and attend or teach at workshops. “Statistical physics has been strong at ICTP. And I’ve seen the great impact ICTP has had for scientists in developing countries, creating real opportunities for scientists.”

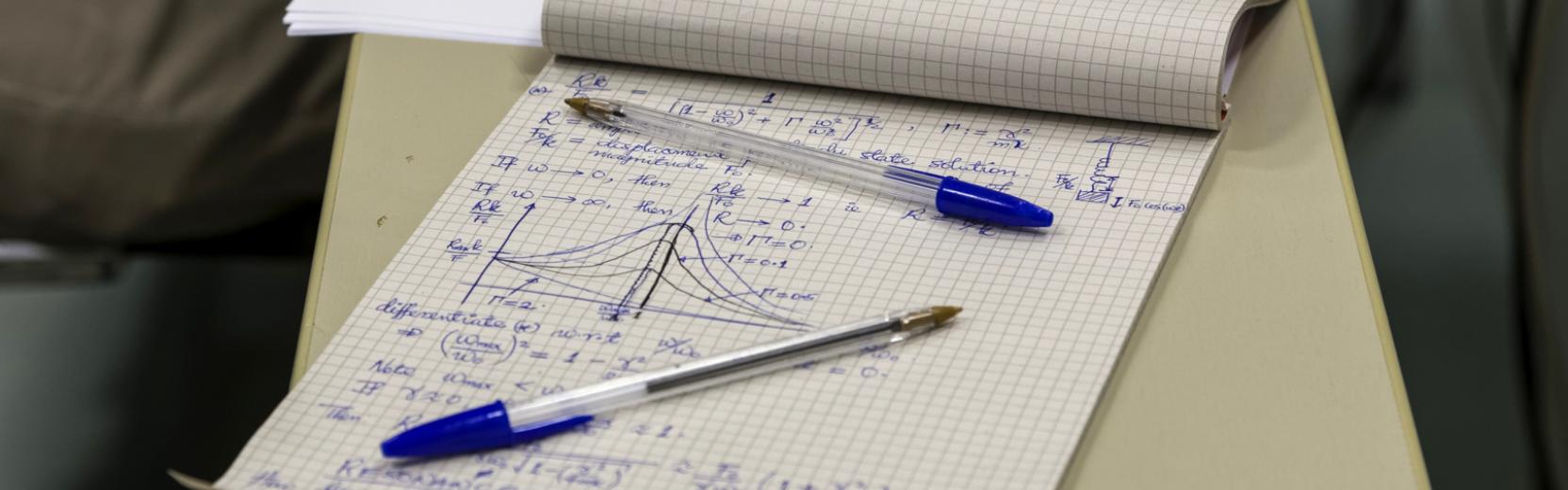

Since 2012, Mézard has served as the director of the École normale supérieure (ENS) in Paris, balancing his research with the demands of leading the prestigious institution. “ENS is a fascinating place, and absolutely outstanding university,” says Mézard. “I think it’s really one of these places that I can have an impact.” With less time for research, he has chosen to focus on information theory and machine learning. “Machine learning is a kind of a technological revolution, a new type of machine that can help human beings,” Mézard explains. “The first industrial revolution was helping us in terms of strength, of physical power, and we have had many generations of machines helping us with intellectual tasks, for the first time now I think they have gone through a major step and they can help us in rather sophisticated specific tasks. But on the theoretical side of this step forward, the progress has been rather slow.”

“In the first industrial revolution, the steam engine was invented and used more than one century before we had thermodynamics,” says Mézard, suggesting that a similar situation may be happening with machine learning. “I am fascinated by these new developments of machine learning and artificial intelligence because I really think that what has taken place in the last six, seven years has been an incredible technological progress, but we don’t have the intellectual framework, not yet. There are still many aspects of learning and deep networks we don’t understand. I am rather thrilled by this situation, I think it’s an interesting challenge.”

------ Kelsey Calhoun