An analysis of three milk teeth belonging to Neanderthal children who lived between 70,000 and 45,000 years ago in north-eastern Italy showed that their weaning age was very similar to modern humans. The discovery disproves theories that differences in child development and nursing strategies contributed to the Neanderthals’ demise.

Results of the analysis, which was carried out by a consortium of research institutes including ICTP, have been published in the 2 November edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The interdisciplinary analyses of the teeth made it possible to reconstruct the development and weaning times of Neanderthal infants. The process of enamel growth produces microscopic lines, similar to the growth rings of trees, from which it is possible to obtain information through histological analysis techniques. By combining this information with data on the chemical composition obtained with mass spectrometry, the scholars were able to establish that the Neanderthal children began eating solid food between five and six months of age.

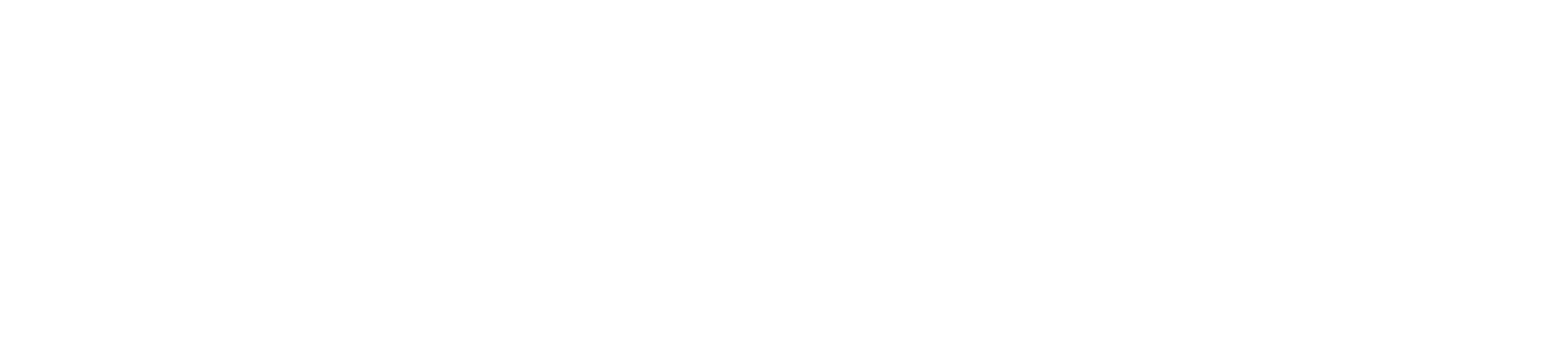

ICTP scientists Claudio Tuniz and Federico Bernardini, co-authors of the study, analyse ancient human teeth using X-ray microtomography (micro CT) at ICTP's Multidisciplinary Laboratory. The MLab's micro CT is the only such scanner in Italy dedicated to palaeontology and anthropology. This technique uses X-rays to develop a high-resolution, 3D image of an object, inside and out. Micro CT and optical imaging, combined with isotopic and chemical analyses, shed new knowledge about Neanderthal early life.

"This study shows that Neanderthal children had weaning time similar to Homo sapiens'," says Tuniz.

"The beginning of weaning is connected to the physiology of infants more than to cultural factors," adds Alessia Nava, of the DANTE - Diet and ANcient TEchnology Laboratory at the Department of Odontostomatological and Maxillofacial Sciences at La Sapienza University in Rome, now a Marie Curie researcher at the University of Kent (UK) and co-first author of the study. "For modern humans, in fact, regardless of the type of culture and society, the introduction of solid food into the diet takes place around the sixth month, when the child begins to need a greater energy intake: now they know that the same timing also applied to the Neanderthals.”

This new information allows the reconstruction of important characteristics and behaviours of Neanderthals. In particular, it makes it possible to exclude the theory that the demise of the Neanderthal population could be linked to longer weaning times than Homo sapiens, an element that would have led to lower fertility.

"The results of this study show that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens share a similar energy demand during early childhood and a similar rate of growth," explains Stefano Benazzi, professor at the University of Bologna, one of the study coordinators. “These elements suggest that Neanderthal infants must have had a similar weight to that of our infants: this would also indicate a similar gestational history, a similar developmental process in the early stages of life and perhaps even a possible interval between pregnancies shorter than what has been thought so far.”

The three milk teeth at the centre of the study were found in a limited area of north-eastern Italy, between the current provinces of Vicenza and Verona. Along with information on the diet and growth process of children, the research uncovered information on the movements of Neanderthal groups that inhabited that region.

“They moved less than previously assumed,” says Wolfgang Müller, a professor at Goethe University Frankfurt (Germany), one of the study coordinators. "The analysis of strontium isotopes present in the teeth indicates that these children spent most of their time in the vicinity of their place of origin: a behaviour that denotes a modern mentality, probably linked to a careful use of the resources available to them in that region."

Tuniz points out that in addition to similar development, weaning time and fertility rate, Neanderthals share with Homo sapiens other characteristics such as a vocal system suitable for complex language, brain size and many cognitive traits. Genetic analyses show the evidence of very close encounters between males and females of the two human species. "Hence, the silver bullet responsible for their demise is yet to be found," he explains. "Probably, both our Darwinian success and their extinction are best seen as the culmination of a spiral of events combining biological, environmental, cultural and social mechanisms."

The title of the PNAS article is "Early life of Neanderthals". (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2011765117)

Scholars participating in the research represent numerous fields, including physics, chemistry, geology, paleoanthropology, archaeology, paleoecology, histology and medicine. They are affiliated with the following institutions: the University of Bologna, the University of Kent (United Kingdom), the Goethe University Frankfurt (Germany), the University of Ferrara, the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, the Institute of Environmental Geology and Geoengineering (IGAG) - CNR, ICTP, the University of Florence, the Sapienza University of Rome, the Natural History Museum of London (United Kingdom).