For a young person, having a role model can affect greatly their life path. In the case of Eyoab Bahiru, from Bishoftu, Ethiopia, this role model happens to be Albert Einstein. Bahiru’s interest in Einstein’s relativity theory eventually brought him to Trieste this year to complete ICTP’s Postgraduate Diploma Programme in the section of High Energy, Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics.

“I looked at the courses and at the professors, and it was perfect, it was everything that I ever wanted,” said Bahiru, who found out about ICTP’s Diploma Programme by coincidence. “A friend of mine mentioned it while we were talking about our future plans.” He found the programme very appealing because of the richness and the variety of the courses, and he recognised the professors teaching the courses as leading experts in their respective fields. “I was also applying to other places, to some of which I got accepted,” added Bahiru, “but I chose to come here, and I am very happy about that choice.”

Bahiru’s path towards science began very early. He has loved mathematics since grade school, and decided that he wanted to be a mathematician when he was in primary school. But when he was in high school, a teacher mentioned something about ‘the twin paradox’, a famous thought experiment about relativity. It attracted his attention, and learning more about it sparked Bahiru’s curiosity and led him to ask his teacher for more information. This is how he got his hands on his first physics book, and from that moment on, he read and studied all he could about the theory of relativity. His admiration for Albert Einstein grew with each page, as he recognized the incredible intellectual and scientific effort that went into the development of Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity.

A few years since encountering relativity, Bahiru has successfully completed the Diploma Programme at ICTP, with a thesis that springs from the Einstein theory of gravity that he has studied for so long. “My main goal is to understand something more about the beginning of the universe,” said Bahiru. “We have a really good standard model of cosmology, but it is not suitable to describe the first few seconds after the Big Bang, which still no other theory in modern physics can describe. Before a few moments after the Big Bang,” he added, “we don’t know what to do. To describe the first moments from where everything started, we would need some kind of quantum gravity, that is, some theory of gravity that describes what happened at a subatomic level.”

Scientists are considering a few candidates for this role. The most well-known is string theory, which has been studied for many years as a promising way to address important questions in fundamental physics. Another option is what Bahiru is studying, the gauge/gravity duality, a new perspective to look at two previously known theories – gauge theory and string theory – that may have new useful insights to the beginning of the universe.

“At first, it looks very difficult because you need to understand a lot of things,” said Bahiru, who studied how gravitational dynamics emerge from the quantum phenomenon of entanglement in his Diploma thesis, with the help of his adviser, ICTP’s Kyriakos Papadodimas. “But after a while it gets easier, and you can see all the potential of this idea. I hope that in a few years we could see something new coming from this field.”

Now that he has completed the Diploma Programme, Bahiru will stay in Trieste for four more years, having been accepted for a PhD at SISSA (the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy) in the section of Theoretical Particle Physics, starting from next October.

“I think that now that I arrived where I am now, and have the potential to go even further, my family is rather happy with my career choices,” said Bahiru. “But when I first decided to study physics at university, most of them were quite upset. Everyone wanted me to study medicine or engineering, like my father, because those are careers where you can earn more money.”

Studying physics in Ethiopia, he said, often means becoming a high school teacher, which was not exactly what he had in mind. Moreover, getting into high level science research is not common in his home country. According to the 2015 UNESCO Science Report, even though almost 40% of university students in Ethiopia study science at the Bachelor’s or Master’s level, only 0.2% of them go on to do a PhD in science. “Eventually, my father allowed me to do physics, because he wanted me to follow my own heart,” recalls Bahiru. Now, he is the only scientist in his family, and he hopes that there will be more in the future.

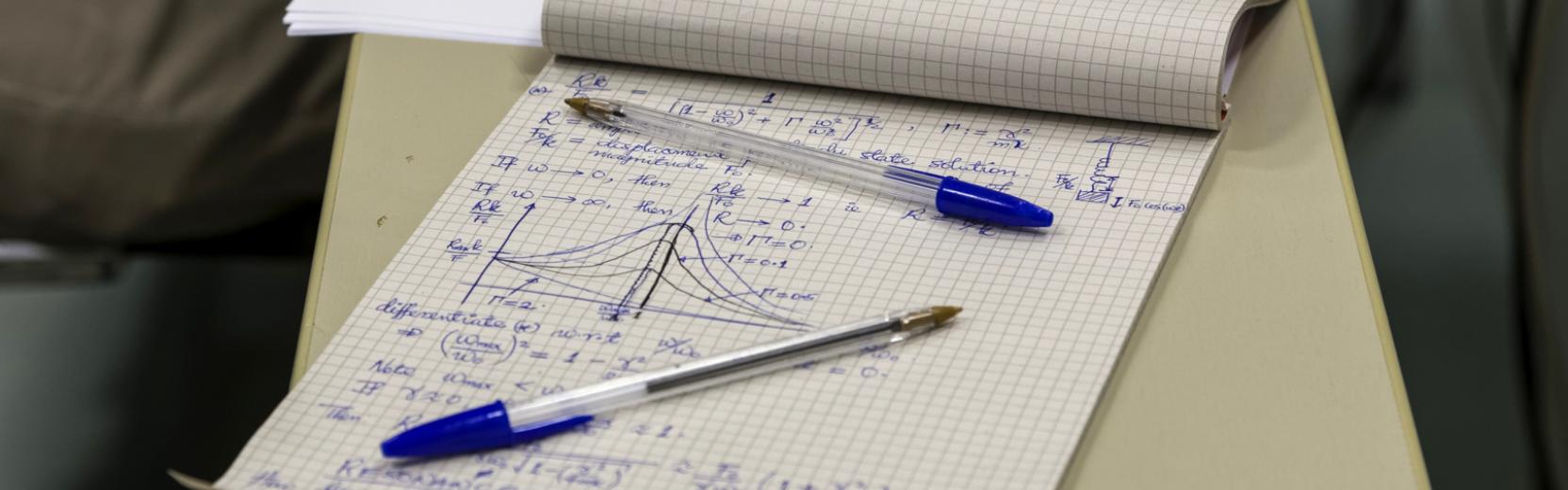

One of the aspects of ICTP that Bahiru recalls most fondly is the pervasive and informal presence of science in the whole institute. “Everywhere you go in the Center there is physics. People talk about physics in the cafeteria, in the canteen, and in every corner there is a blackboard, so whenever you are you can talk about physics with anyone,” said Bahiru with a sparkle in his eyes. “And also the professors are really friendly, down to Earth and very keen to help us. You can discuss with them any question you have at lunch or while drinking coffee, it’s really good.”

---- Marina Menga