Say the phrase "experimental physics" and the imagination often runs to the huge facilities and big collaborations required for studies in fields like particle physics or gravitational astronomy, such as CERN or LIGO. These large research projects require a lot of funding and specialized equipment to capitalize on their potential, but an emerging group of researchers thinks that's not the only way to do experimental physics. The opposite of these big projects is so-called tabletop science: just a little investment is required to build a small experiment able to produce high-quality results in complex systems physics.

Exploring and teaching the potential of tabletop science was precisely the aim of the 8th edition of the Hands-On Research in Complex Systems School (17-29 July), hosted and sponsored by ICTP and co-sponsored by the American Physical Society (APS), the UK Institute of Physics (IOP) and the European Physical Society (EPS). During the two-week school, a cohort of around 60 graduate students and young faculty from developing countries were introduced to table-top research on problems at the frontiers of science. They worked closely with major scientists to address questions in fields ranging from fluid dynamics to chaos, and from biological molecular motors to self assembly of colloidal systems.

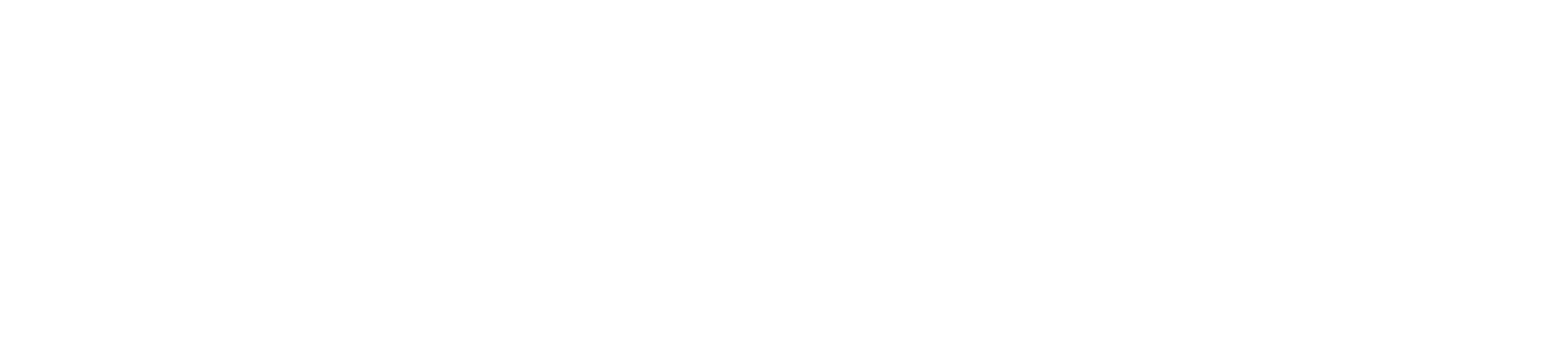

From physical to chemical and biological systems, the course established eight small lab-facilities to conduct experiments with modern--yet inexpensive--digital instrumentation. One of the School's commitments, in fact, is to maintain the budget for each of the table-labs to below 2000 euros. Many experiments involved capturing data on video; participants were then taught new approaches to analyse these data streams.

The participants complemented their experimental work with mathematical modelling and data analysis using the mathematical software tool Matlab, explains Pietro Cicuta, scientist at the Biological and Soft Systems sector of the Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge, and one of the school directors. “In the optical laboratory, for instance, we provided a demonstration of directed and Brownian motion in algae. We imaged a model organism named Clamydomonas, which swims thanks to a structure called flagellum. This flagellum has the same molecular structure conserved even in superior species and well preserved during evolution.” Cicuta explains that in the laboratory they provided the knowledge to build a low cost image-analysis tool, able to follow the movements of the algae, without the use of sophisticated software or expensive microscopes: “Even in this period of science budgets being cut across the world, driving research fields to focus more on theoretical rather than experimental investigations, we want to demonstrate that tabletop projects provide a low-cost way to do competitive experimental science.”

As well as demonstrating potentially striking results achievable with limited funding, the Hands-On School (following a programme fine-tuned over its eight-year history) also focused on other professional capabilities considered crucial for developing a successful scientific career. “Our idea was to help the participants improve their skills in scientific communication,” says school co-director Michael Schatz, scientist at the Center for Nonlinear Science, Georgia Institute of Technology. "Considering science as an enterprise that is carried out as a community, scientific communication is an important aspect that we wanted to underline. At the School, participants presented their work in brief talks and posters; before the presentations, we met in small groups where both faculty and participants provided feedback to attendees to help make their talks and posters more effective.” Interpersonal skills like these are broadly sought after in scientists, Schatz suggests, although the opportunities to improve them are quite rare — both in developing and developed countries.

Tabletop experiments, involving small teams and modest budgets, and a discovery cycle of just a few years, represent a style of conducting science that is thriving in developed countries and should inspire experimental activity also in developing countries. Shatz believes that the continued success of the School depends not only on its attractiveness as a low-cost way to carry out experiments, but also on its consdierable network of alumni. “To enlarge our impact and extend our range of activities, our idea is to enhance the connections between present and past participants. This year, for instance, we started a pilot programme for a group of young talented researchers, with the aim to bring back the practical knowledge to their laboratories, continue a collaboration, and to publish in top scientific journals,” says the researcher. “We called these efforts extended projects, and we aim to make them one of the trademarks of our success.”

--Alessandro Vitale