Cloudspotting is a serious matter in science. When atmospheric physicists deal with environmental changes, they face an emerging question: how will cloud systems and their organization interact with climate change?

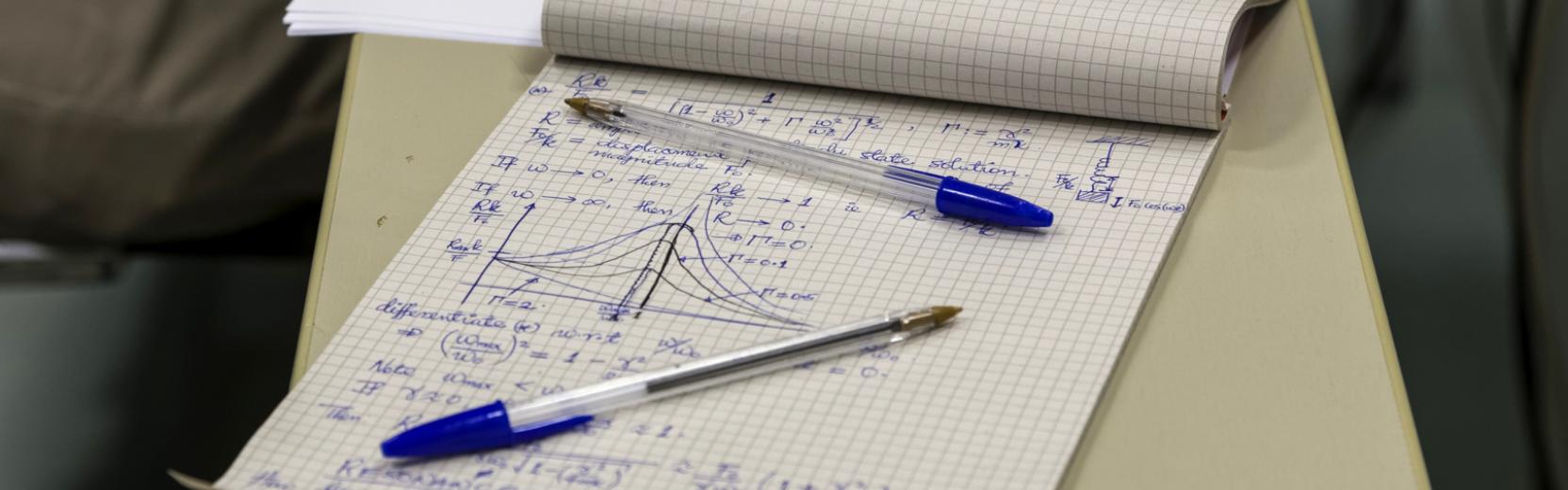

To address this and other issues, ICTP co-hosted the “Conference on Cloud Processes, Circulation and Climate Sensitivity”, together with the Cloud Feedback Model Intercomparison Project (CFMIP), a global research project working to improve assessments of climate change-cloud feedback, and the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), which co-sponsors CFMIP. The CFMIP/WCRP/ICTP international meeting consisted of a four-day conference from 4 to 7 July 2016, with oral and poster sessions focusing on WCRP’s Grand Science Challenge on Clouds, Circulation and Climate Sensitivity. Leading names in the field presented the latest state-of-the-art science regarding cloud physics, the impact on circulation and its variability, modeling and observational constraints on cloud feedback, and climate models using fine scale observations.

When people think of climate change, the discussion often revolves around carbon dioxide. However, the evolution of clouds adds a lot of uncertainty to our knowledge of the future climate. The radiative impact is only one important aspect when considering clouds,explains Sandrine Bony, member of the CFMIP steering committee and senior research scientist for the National Committee of Scientific Research, at Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique in Paris. “For a long time clouds were mainly believed to be important in climate change because they can modulate the amplitude of global warming by reflecting sunlight.” That view has changed, Bony says. "Now we increasingly pay attention to how they affect large-scale circulation. This is getting much more attention this week than past conferences,” Bony explains.

Prior to the meeting, there was an additional opportunity for young scientists coming from around the world to network with the high-level researchers, as ICTP also hosted the Summer School on Aerosol-Cloud Interactions (27 June - 1 July), co-directed by ICTP’s Fabien Solmon, Adrian Tompkins and Wojciech Grabowski, Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Colorado. The school consisted of basic and advanced lectures on the current knowledge of how aerosol particles are formed and evolve in the atmosphere, and how clouds grow from aerosol precursors to major components of the climate system. Computing sessions on cloud and aerosol modeling were also organized, complementing the formal lectures. “When I started working 30 years ago clouds were part of atmospheric physics, but were not that interesting. Now they represent a forefront of climate and climate change research,” says Grabowski, adding, “This could be a good area to build a scientific career, because environmental change is a big issue.” This Summer School is a great opportunity for young climatologists and meteorologists, Grabowski explains, recalling talented young researchers he met while visiting the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology and subsequently encouraged to apply to the ICTP school.

This sentiment was echoed by Bjorn Stevens, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg and another leader of the CFMIP effort: “Students who come here for the conference--and some are already at ICTP for its Postgraduate Diploma Programme--are usually very well prepared. It is a great opportunity, also for us, to learn about talent from developing countries, which is normally much more complicated compared with finding students coming from Europe or America.”

The CFMIP meeting at ICTP was not only important from a scientific perspective. Communicating the science and importance of climate change to the general public, especially in developing counties, remains a pivotal concern for scientists. “We could do a better job involving citizens of emerging nations in the thrill of discovery,” says Stevens. “To face climate change, developing countries are now focusing on preparing for the future, but there is so much that can be learned from the past. To engage them and raise awareness, the question could be: what is (for instance) different in Kenya today, versus 150 years ago? I think it could sensitize citizens much more to the changing of the climate, and their environment, as compared to more hypothetical or abstract arguments,” explains Stevens.

However, climate change is not only an issue for developing countries, and the same goes for science communication, adds Chris Bretherton, co-chair of the CFMIP committee and atmospheric researcher at the University of Washington, in Seattle. “Environmental changes themselves could be an opportunity to get closer to the topic: for instance, in the northwestern US, we have an economy partly based on fishing and growing oysters, which are quite sensitive to ocean temperature and acidification. For instance, it is now hard to grow oysters in our area because increasing levels of carbon dioxide mean ocean acidification hinders oyster larvae from growing shells. All these changes contributed to the birth of a strong citizen science community in our area," explains Bretherton. "As scientists, everyone has their own individual scientific task, but overall there shouldn’t be any doubt that global warming is important."

--Alessandro Vitale