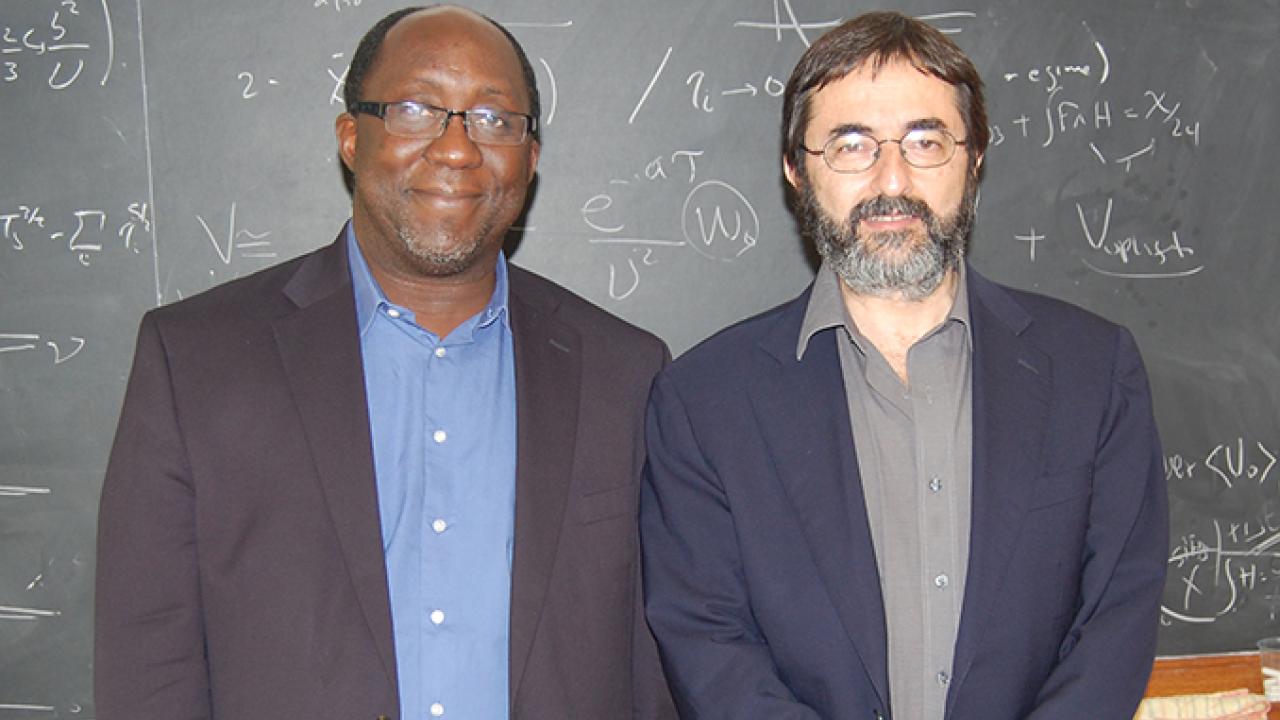

It would be difficult to find a bigger champion of African science than Winston Wole Soboyejo. One of the world’s leading materials scientists, Soboyejo served for three years as president of the African University of Science and Technology (AUST) in Abuja, Nigeria. These days, he is a professor in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at Princeton University, USA, and also serves on ICTP’s Scientific Council. He is using his considerable experience in science development to influence international policy makers through his role as a member of the UN Secretary-General’s Scientific Advisory Board (UNSAB). Created by Ban Ki-moon in 2013, the UNSAB comprises 26 eminent scientists from diverse disciplines of relevance to sustainable development, with the aim to strengthen the interface between science, policy and society.

The UNSAB recently convened its latest meeting in Trieste at ICTP, by invitation of the Italian Government. While he was here at the Centre, Soboyejo took some time to share his views on brain drain, the enduring value of human interaction in a digital age, and how support for basic sciences is crucial for economic and social development.

Is brain drain still a problem in developing countries?

I like to look at a “brain circulation” idea, as opposed to the idea of a brain drain, in that you need to have the opportunity to help people help themselves intellectually in various ways. If people stay in one place, they never get exposed to ideas beyond that region, so in that sense I believe very much in the idea of brain circulation, where you go to different places to get exposed to different ideas and you really build capacity to the very highest levels.

Once you’ve done that, then the question is, where’s the opportunity space for you to really contribute and give back? For some people it means they return to work at a university in a developing country. But even then, it’s not a good idea to only just stay there, it’s good to circulate in and out of other places such as ICTP and keep getting exposed to good ideas that allow you to grow and keep exploring new frontiers. A good example of that is [ICTP Scientific Council member] Professor Francis Allotey, who has been doing this at ICTP for the past 50 years.

Another potential model is like an intermediate model. Somebody like myself, who is educated outside of Africa, in some sense starts a career outside of Africa but explores ways to go back to teach and advise PhD students and perhaps spends up to four years in my case on the ground working on some specific projects. Even when that person goes away from Africa you can still continue to receive people in your lab in some way.

Then there’s a third approach where you go for short visits, teach a short course, help with a specific project, help with an advisory board--you bring all of that experience you have back and you keep rotating in and out in a way that allows you to share knowledge with the next generation of people in a field.

What then matters is how you circulate people, and build knowledge and human capacity and human potential, whereas often were you to insist that everyone stay in the same place, with the same knowledge and the same limitations, you don’t quite achieve the same outcome as you do with the circulation model.

What are some of the biggest challenges facing science in developing countries, in implementing and supporting basic sciences?

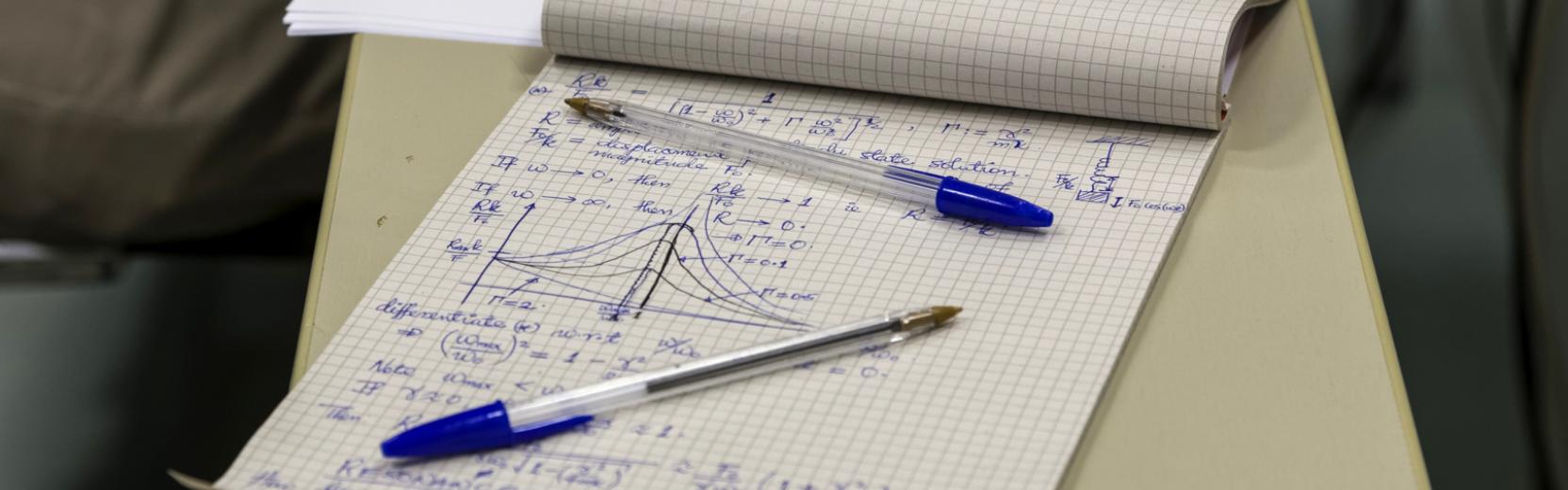

I think there’s some confusion in developing countries about basic vs. applied science. Many countries believe that applied science alone addresses their needs without recognizing that basic and applied science are two sides of the same coin. If you don’t have strong basic sciences you actually cannot do very unique and original applied science. If that strength is missing because you choose to focus only on applied science, the effectiveness and competitiveness of what you do on the applied science side is very limited. I think that there needs to be an environment that promotes research in both the basic and applied science arena, and you need to separate the funding for research from that for education. Many countries invest about 1% of GDP in science and technology, btu when you look at how that investment is distributed it’s .9% for education and .1% in some kind of research.

There needs to be more genuine efforts to gradually scale up the support base for science and technology research. Why does this destroy the system if you don’t invest? You will have few innovations, and even worse, you don’t have the right quality people teaching science and engineering at the university level, which means that the quality of your graduates in science and technology is not sufficient to compete globally. Even worse is that the people who teach science at the primary and secondary schools do not have the right level of education to produce people for university education or people who can teach. So the whole standard of the country drops, and then you cannot compete or develop. In my opinion, there is no country that can exist without that investment. The support of basic science and mathematics is often what gives you the edge. For many countries, this investment is strategic and potentially transformational.

How can policy makers in developing countries be convinced of the value of investing in basic sciences? As a member of the UNSAB, what role do you think the UN can play in this?

Beyond the development of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), there should be in the next phase some guidelines given on strategic investments in science and technology by countries in terms of threshold levels to be reached. Even for donor countries, there could be some guidelines set to say that perhaps 20% of donor funds to developing countries should focus on science and technology education and research that allow those countries to address sustainable development goals. As simple as that sounds, it would give some guidance to many countries across the world that have this objective to use science and technology to develop their economies and the well-being of their own countries. In the absence of this, it becomes a challenge.

One potentially interesting model that the UN could play a role in is the establishment of local research centres or labs within a UN framework that has internationally calibrated practices. If that were done, different countries could focus on areas where they have niche interests. There could be an environment where the diaspora could return to and know that they’ll have proper retirements and long-term funding for a research agenda with a certain framework that works. You could then have a network of UN category 1 and 2 research centres that do research that focus on developing new ideas that can impact the developmental goals of those countries.

How can ICTP maintain its relevance in a world that is becoming increasingly interconnected thanks to technological advances?

I think there is still value in human interaction beyond electronic interactions. This process of bringing people from multiple cultures to a place like ICTP and exposing them not only to new ideas and knowledge but also to new cultures, is an important first step. And then diffusing them back to their home countries where they can continue to grow and contribute is currently where we are at. The next step is the whole notion of building ICTP centres across the world, which in my opinion offers opportunity for many of the people who have been trained by ICTP as well as future generations and others that want to contribute, to interact regionally.

So now the question becomes, how do you leverage electronic communication, how do you leverage video conferencing, how do you leverage various ways of interacting, in ways that increase the impact of that interaction? These questions are relevant to new ways of teaching, of doing research. One can now begin to think about virtual research groups, as well as virtual classrooms, in ways that scale the impact. In that sense, there is the possibility to build on the ICTP model, but it has to be done in careful steps, because what you don’t want to do is to lose the ICTP quality and branding by trying too many experiments without some careful thinking , planning and execution. I do think that ICTP is moving in the right direction by trying to have these centres, and I think there is rich potential in working with ICTP alumni who are scattered all across the world, and these regional centres and virtual methods could scale the impact of ICTP globally.