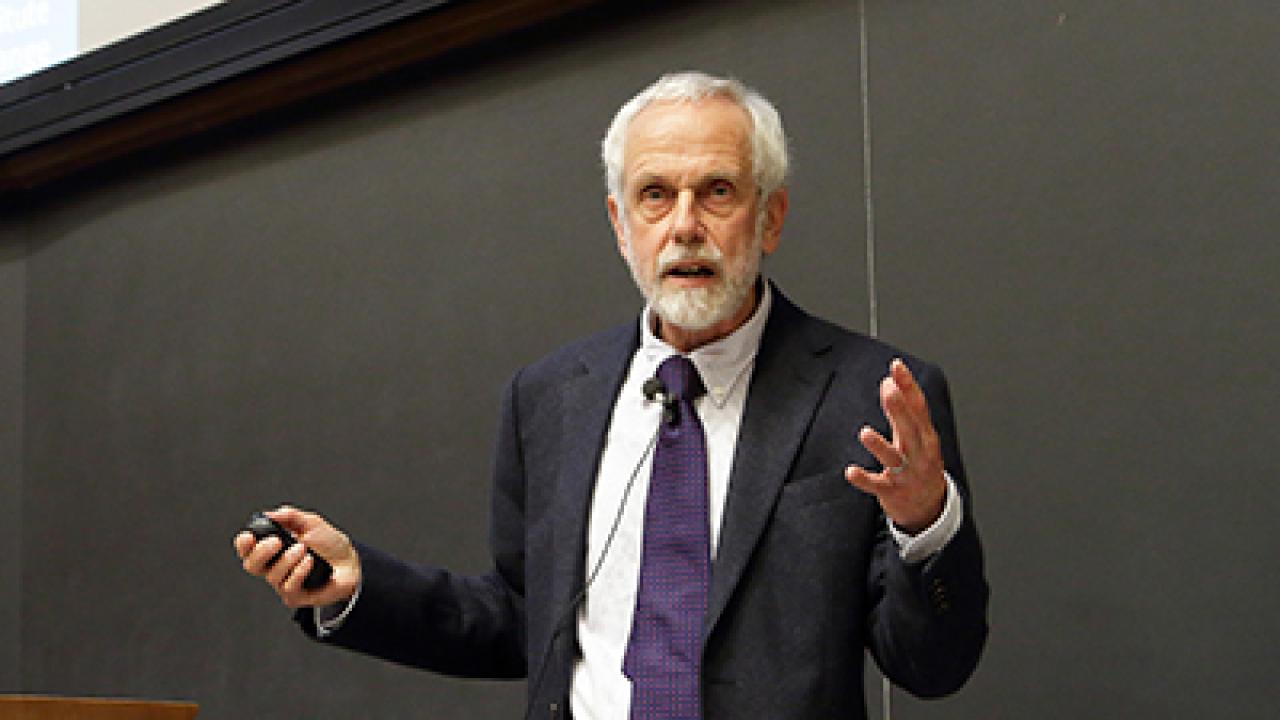

Every year, the Salam Distinguished Lecture Series welcomes a renowned active scientist to ICTP, to give a series of talks covering an overview of recent scientific developments in their field as well as a visionary view of the future. This year the British climatologist Sir Brian Hoskins offered a timely sketch of climate change science and the implications for our rapidly changing planet, drawing on over forty years of a successful career as well as considerable experience communicating that science to both the public and policy makers.

The recorded lectures are available on ICTP's YouTube page.

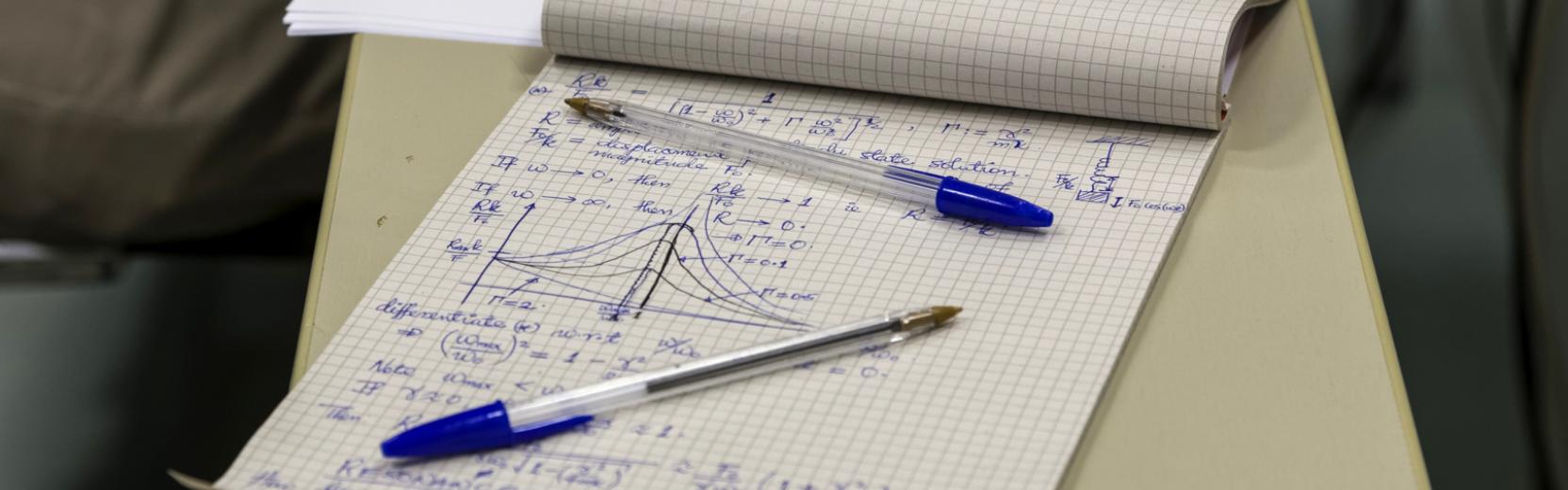

Speaking to a wide audience of ICTP scientists and students as well as many others watching via livestream, Hoskins' first of three lectures was entitled "The Climate System and Roles of the Atmosphere and Ocean." This was especially appropriate for a climatologist who started his career studying the fluid mechanics of the atmosphere and oceans. In fact, Hoskins holds a PhD in mathematics, but quickly made his way over to meteorology and climatology, applying math to geophysical questions.

"I could do pure maths, but I couldn't see why," he recalls, instead becoming quickly interested in applied mathematics as an undergraduate, viewing questions about the atmosphere and oceans as mathematical problems. After a post-doc year in the USA, he took a job at the University of Reading's Meteorology Department, beginning a life-long quest to understand how weather and climate really work. Hoskins, who is still an active researcher at Reading, says, "It was a great time to study weather, because computer models of the atmosphere were starting to be something you could really use, and satellite data enabled global analyses of the weather to be routinely available."

Hoskins' successful career includes a stint of six years as founding director of The Grantham Institute, which focuses on encouraging inter-disciplinary research and influencing climate related policy in business, industry and government. Based at Imperial College London, Grantham unites the basic science Hoskins does, as well as expertise in "many of the technologies I think we need, things like photovoltaics," Hoskins says, adding, "I firmly believe that any advice we give should be based on the very best science and technology."

Intrinsic in that science of climate is the understanding that while it's clear global weather patterns are changing, it is difficult to know specifically how they will morph in the future. "Understanding how climate phenomena or drivers are going to change is crucial," he explains. "We know we're doing something pretty dangerous with Earth's climate, but we don't really know any details of what may happen." Any climate predictions also involve probabilities, so it's difficult to present a simple picture to policy makers, which is where resources like the Grantham Institute come in. "There's variability on all time scales and there always will be," Hoskins points out.

"On one of my forays into 10 Downing Street -- there was some meeting with Margaret Thatcher -- I said there could be a decade where the climate system doesn't warm, given the variability." That actually ended up happening, with little global temperature average rise in the 2000s. "But climate change hadn't gone away, so politically it's very difficult. You have to have some idea of the longer timescale. The timescale of a politician can be five years if you're lucky, five minutes if you're not."

Getting politicians to pay attention is one of the massive challenges that accompanies climate change, challenges which Hoskins outlined in his final talk at ICTP, entitled The Challenge of Climate Change. Unfortunately, many of those challenges will first be confronted in developing countries, Hoskins says. "Developing countries tend to be in the hot parts of the world, and there are many climate change issues associated with agriculture and rainfall. We're all vulnerable, but those are the places we should really worry about."

That worldwide vulnerability shows that besides learning how to adapt to changing climate averages and extreme weather, offset actions and drastic emission reductions are also needed. There is a huge amount of work still to be done to avoid a growing frequency of extreme weather events such as the Alberta and Moscow wildfires, Hurricane Katrina, or Typhoon Haiyan. Despite this, Hoskins is pleasantly surprised at how nations are coming together to take action.

He singles out the recent climate talks in Paris as a positive step forward. "Clearly there's a long way to go, but this move to a point where basically all the countries of the world are not questioning climate change, they've accepted it and the need to do something about it -- that is amazing." With luck, climate science will get the attention it needs in the realm of policy as the world struggles with the challenges of climate change.

--Kelsey Calhoun